San Francisco Dispatch, Los Angeles Express, Los Angeles Herald

1830-1897

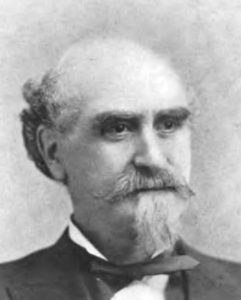

Joseph Ayers was a peripatetic, restless printer-newspaperman-miner who finally settled in Los Angeles after cramming a lifetime of adventure into two decades of frontier life.

James Joseph Ayers

Ayers was born in Glasgow, Scotland, on Aug. 27, 1830. His parents migrated to America the next year, and young Ayers was reared in New York City or New Jersey, depending on historical accounts, where he was trained as a printer “at the case.” When 18 he traveled to St. Louis and became Sunday editor of the Republican, but he soon tired of that job and took a river boat for New Orleans in February 1849. When the gold fever struck, Ayers embarked for Panama, headed for the California diggings. Because the Panama steamers were so crowded, the group he was traveling with built their own boat and sailed to Cape San Lucas, where they were shipwrecked. Ayers swam ashore in Baja California and walked to San Diego. (James McClatchy of The Sacramento Bee had a similar experience, and it is even possible the two were companions on the long march from lower California to San Diego.)

After some weeks wasted in the gold fields, Ayers returned to San Francisco and with another printer started a weekly newspaper, The Public Balance. Whatever success the venture had was cut short in the disastrous fire of 1851. Burned out and busted, Ayers went to the Calaveras River and was luckier on his second effort as a miner. He became part-owner of a claim at Mokelumne Hill that later produced more than $2 million in gold, but by that time Ayers had sold out and returned to a newspaper office.

In 1852, Ayers joined Henry Hamilton and Harry de Courcey in founding the Calaveras Chronicle. Two years later, Ayers was back in San Francisco as an editor of the Herald, a career ended abruptly by merchants who forced the newspaper out of business because of its anti-vigilante stand.

Again “at liberty,” Ayers joined five other printers in founding the San Francisco Call, where he became an editor in 1856. Throughout the exciting days of the Civil War, marked by appeals for a western railroad and continued efforts to connect the west with the east, Ayers stayed at this bustling post.

Ten years of stability proved only that Ayers’ wanderlust was not gone. In 1866 he sold his Call interest and headed for the Hawaiian Islands. There he became publisher of the Hawaiian Herald, but possibly because of his chronic asthma, Ayers was soon back in California.

In 1867, he founded the San Francisco Dispatch; in 1869 he edited the Virginia City, Nev., Territorial Enterprise; and in 1869 he published the White Pine Inland Empire. By 1872 he was headed southward and paused for a time at San Luis Obispo to edit the Tribune.

In 1873 a group of Los Angeles businessmen who had been fighting the railroads formed a syndicate and purchased the Los Angeles Express, then placed Joseph D. Lynch and Ayers in charge.

An ardent Democrat, Ayers served in the 1878 State Constitutional Convention and was active in the campaign of General George Stoneman for governor. That Convention framed the foundation of the laws of California, where Ayers helped to ensure that both men and women could attend the University of California. The only other Convention prior to 1878 had been held in 1849. The 1878-79 Convention, which rewrote the entire California Constitution, met for five months and four days.

In 1883 he sold his interest in the Express, and was appointed State Printer by Governor Stoneman. He held the office for four years. During Colonel Ayers’ incumbency it became necessary to largely increase the capacity of the office, so that under the law the state could print, electrotype and bind the textbooks of the public schools.

This was a new and formidable departure in a public institution, and any serious mistake would have given the undertaking a setback from which it would hardly have recovered. California was the first state to print its own schoolbooks. To prepare for the work Colonel Ayers was compelled to reorganize the entire state printing office, and to go East, inspect all the latest and most improved presses and machinery, and select the best and most approved.

The result was that he made the state printing office one of the most complete establishments in the United States if not absolutely the most complete. If the publishing of our own textbooks at cost has been a success, it is due more to the intelligent, practical and faithful efforts of Colonel James J. Ayers than to any other man.

While in Sacramento, Ayers married a local school teacher, Charlotte Slater, and returned to Los Angeles with his bride in 1887. With Lynch again as his partner, Ayers bought the Los Angeles Herald and was its editor until 1894, when ill health forced him to retire. He died on Nov. 12, 1897, at his Azusa home. He was a member of the Society of California Pioneers. He also was a trustee of the California State Library from 1885 to 1886.

Ayers was self-educated and wherever he settled soon established a reputation as a scholar. He studied Shakespeare avidly, read and wrote poetry, and was regarded as “one who fills the position of editor as cleverly as he uses the [printer’s] stick.”