To countless young journalists, Frank McCulloch was the adult in the newsroom. To veteran reporters, he was a sage counsel, advising them on the intricacies of complicated and controversial stories. To journalists everywhere, he was a towering figure who stood for the highest principles. Here, his friend and colleague of 57 years, author, publisher and professor Warren Lerude, describes McCulloch’s extraordinary life.

By Warren Lerude

Frank McCulloch, the son of a pioneer Nevada ranch family who served as a combat war correspondent and led major American news organizations distinguishing himself as an icon for a free press, died on May 14, 2018. He was 98. His family was close by at a Santa Rosa, CA, nursing facility where he had been treated for a brief illness.

McCulloch served as a reporter, editor and bureau chief for Time-Life News Service bureaus ranging from New York and Washington, D.C., to Dallas and Los Angeles. He served as Southeast Asia bureau chief in Hong Kong and Saigon covering the Vietnam war and in top editor positions at the Los Angeles Times, the national McClatchy newspaper company based at the Sacramento Bee and the San Francisco Examiner.

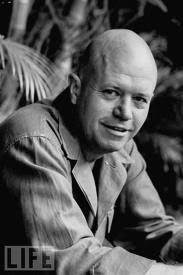

Frank at Life Magazine. Photos courtesy of Warren Lerude.

Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism in New York presented McCulloch its highest award in l984 “for singular journalistic performance in the public interest” and “overarching accomplishment and distinguished service to journalism”.

McCulloch both championed and questioned his profession, saying at a retirement dinner in Los Angeles in l964: “We admit the free press is not what it should be, and probably never will be. But the inescapable truth is, it’s all we’ve got. For better or worse, so long as this remains an open society, you and we — a free people and a free press — are stuck with each other. Shouldn’t it behoove both of us to try to understand each other better?”

Pulitzer Prize-winning war correspondent and author David Halberstam, commended McCulloch as he received the Center for Investigative Reporting’s prestigious 2009 Founders Muckraker Award in San Francisco:

“I speak for a great many others in different venues where Frank worked, and was admired, and always made a difference. Some of us had a sense of his iconic status for a long time, going back as far as l967” when McCulloch covered the Vietnam war as “a marvelous reporter”.

President Johnson was enraged by McCulloch’s Vietnam reporting in l966 that he planned to build up American forces to 545,000. Halberstam recalled a senior reporter in Washington raised the topic with Johnson, “who famously answered that Time’s bald-headed Saigon bureau chief had been wandering around in the sun without a hat and was addled. Well, they loved that in the upper levels of the Time hierarchy. The fact that the president knew that Time’s man was bald.” McCulloch’s own colleagues in the Time-Life Washington bureau were critical but by 1968 the forces had grown to that number.

“I wasn’t any genius,” McCulloch said in an interview published in the University of Nevada Silver & Blue alumni magazine years later (l992). “I just had the sources.”

A meeting with Indonesia’s President Sukarno.

One disagreeable source, Indonesian ruler Sukarno, confronted McCulloch because of his reporting in Time. McCulloch recalled their intense, face to face standoff. “He was threatening to throw me out of the country, and I told him I didn’t think that would be a very good idea for either of us.” Sukarno backed down.

McCulloch was credited at the San Francisco program for inspiring a generation of reporters, including Halberstam, Karsten Prager of Time Magazine, Lowell Bergman of The New York Times and PBS Frontline and scores of others.

Young reporters saw McCulloch as a visionary. He predicted the death of once robust Life, Look and the Saturday Evening Post national magazines, which he prophesied being forced to give way to television’s dramatically moving photo journalism, increased depth reporting in major newspapers and a proliferation of specialized topical magazines.

He encouraged one young Associated Press reporter to join his staff as a business writer at the Los Angeles Times in 1962 with a promise of spirited competition to beat back the invasion of

The New York Times in a newly planned West Coast edition. He confided to the reporter ahead of any official announcement of the creation of The Washington Post/Los Angeles Times news service to compete with the well established new service of The New York Times.

McCulloch wrote many Time Magazine cover stories, including a l955 piece on Justice Thurgood Marshall of the U.S. Supreme Court, when the cover stories had a unique status in national journalism. He covered a range of presidents from Truman to Johnson, Nixon and Ford as well as Generals Curtis LeMay and William C. Westmoreland and writers John Steinbeck and Ernest Hemingway.

McCulloch was the last reporter to interview billionaire Howard Hughes when, in l958, the Hollywood and aviation celebrity took him on a flight over Southern California and Arizona in a prototype of the 707 to predict a new era of jet plane passenger traffic.

McCulloch made news himself in l972 when author Clifford Irving claimed to have interviewed the by-then reclusive Hughes for a book and Life Magazine serialized the story as authentic. Hughes called McCulloch, then working in Time-Life New York headquarters, to reveal it as a hoax, and McCulloch stopped the Life presses in Chicago to kill the magazine’s serialization, upsetting his bosses at Time-Life.

“I did it on my own,” he said with a chuckle in the Silver & Blue story. “It didn’t sit too well with my superiors. But it would have been a lot worse if the edition had continued to run.”

The dramatic turn of events eventually was made into a movie, The Hoax, starring actor Richard Gere. Another actor played the bald-headed McCulloch character.

McCulloch was born in Fernley, Nev., about thirty miles east of Reno, on Jan. 26, 1920 to ranchers Frank and Freida McCulloch and educated in rural classrooms and at Reno High School. He worked at his school paper but really broke into journalism as the editor in charge of the University of Nevada student newspaper Sagebrush in Reno, graduating with Phi Beta Kappa honors in 1941.

While in college, McCulloch met Jakie Caldwell, the daughter of a nearby town veterinarian who inspected McCulloch’s father’s cattle

Frank and Jakie in the early 1940s.

for the state of Nevada. A student away in a college in Oregon, she was visiting her parents in their home in Yerington. “It was love at first sight,” a family member said. McCulloch courted her on horseback rides and soon proposed. They were married after graduating from college on March 1, 1942 at the home of her parents, George and Faye Caldwell.

McCulloch often paid tribute to his alma mater, joking with friends: “If it weren’t for that journalism school, I‘d still be bucking bales of hay on the ranch in Nevada.”

The university presented him an honorary doctorate when he returned to the campus as commencement speaker in 1967 and named him a Distinguished Nevadan in 2018. He was further honored by his alma mater when the Reynolds School of Journalism created the endowed Frank McCulloch Courage in Journalism Award, given annually to journalists of national achievement, and the student newspaper designated the Frank McCulloch Lifetime Achievement Award for distinguished alumni. He was selected twice as the Distinguished Scripps Lecturer that honored fellow Nevada journalism graduate Ted Scripps of the Scripps Howard news organization.

After graduation, McCulloch worked for United Press in San Francisco as a reporter, then served in the U.S. Marine Corps from 1942 to 1945. He served as a reporter covering crime, sports and politics for the Reno Evening Gazette from 1946 to 1953, then joined Time-Life News Service where he began his long news magazine career. He was a founder of Learning Magazine in 1972.

McCulloch, recipient of the Society of Professional Journalists Freedom of Information Award in 1983, reflected on his career in a 2012 Nevada alumni magazine story, saying he was proud of “starting, maintaining and establishing investigative reporting at the Los Angeles Times, The Sacramento Bee and San Francisco Examiner. Investigative reporting deals with misdeeds, inefficiency or any kind of corruption within institutions that have considerable public consequence. It inevitably leads to libel suits.”

One highly controversial libel suit involved U.S. Sen. Paul Laxalt, R-Nevada, and investigative reports in The Sacramento Bee about finances at the Laxalt-owned Ormsby House hotel in Carson City, Nevada’s capital. The story gained national prominence because of Laxalt’s status as close friend to President Reagan and the possibility of Laxalt himself becoming a presidential candidate.

Laxalt challenged the story as defamatory and libelous. McCulloch stood behind it, declaring at a 1983 journalism forum in Reno: “It certainly would not have been published had we not been utterly confident that everything was factual and, in a broader sense, true.” The suit was settled amid a bristling controversy between Laxalt and the McClatchy organization with details not made public.

At the height of the intense libel drama, coffee cups appeared in the Sacramento Bee newsroom proclaiming in bright red ink: “Laxalt Our New Editor Publisher.” McCulloch ironically recalled to a friend how he played basketball for Reno High School against Laxalt at Carson City’s high school.

The Center for Investigative Reporting, at its San Francisco program honoring McCulloch, cited “his passion for investigative reporting” by noting he “was named in seven libel suits — all unsuccessful — during his McClatchy years that helped establish protections from which journalists still benefit today”.

McCulloch was frequently hailed as a journalist’s journalist. When he retired as managing editor of the San Francisco Examiner in 1991, staff writer Harry Jupiter commented: “These are bittersweet days at The Examiner. Reporters don’t usually get misty-eyed at the departure of the boss. But Frank McCulloch is not a typical boss … McCulloch leaves enormous footprints. He has been one of the outstanding movers and shakers in American journalism for 50 years … Even more than his magnificent achievements, there is something else. Heart, if you will. And soul.”

The Examiner published a special edition celebrating — and lamenting — McCulloch’s retirement while noting he would still be on hand in a consulting role.

The boldface headline “GURU GONE” carried a second line of type: “Frank-ly, We Give a Damn.” Still another headline proclaimed McCulloch retires, sort of, after journey from Fernley to Sonoma, noting he and his wife of 49 years, Jakie, would make San Francisco’s wine country suburb their retirement home where their two daughters lived with their families.

He remained a strong voice for the First Amendment against political censorship. In 2014, at age 94, blind in one eye and

Frank McCulloch in 2015.

nearly so in the other, he helped lead a group of journalists across the nation to convince the Pulitzer Prize Board at Columbia University to correct a controversial wrong in the history of American journalism.

McCulloch wrote the group’s lead letter petitioning for a posthumous Pulitzer Prize for Ed Kennedy, who broke the news of the German surrender May 7, 1945, to the Allied Forces. Kennedy was fired by the news service amid claims that he broke an embargo delaying the announcement for political purposes. The AP apologized for the firing 67 years later, acknowledging its error and praising the long-disgraced war correspondent’s work in reporting the historic news.

McCulloch wrote to the Pulitzer Board: “There are two kinds of censorship: Military censorship, to save lives, and political censorship, by means of which one of the combatants tries to bend the press to its will on matters having nothing to do with saving lives. To personalize this, I became intimately familiar with both kinds when I was a combat correspondent during the Vietnam war, when political and policy censorship was largely a failure.

“I believe history will show that it has not been effective in any war. It’s the policy and political kind that Ed Kennedy violated. Throughout his long career as a combat correspondent, Kennedy respected military censorship. The historical record shows that his career was ruined and his reputation destroyed because he did the right thing by reporting the news that the entire world had every right to know.”

McCulloch and the committee of journalists urged the Pulitzer Board to award Kennedy the high honor. It declined to do so without explanation.

In retirement, McCulloch confided to friends that he still dreamed of being back in the newsroom, and he didn’t stray too far from it, continuing to consult with newspapers, talk with journalism students and lend his expertise to the nationally prominent Center for Investigative Reporting in the Bay Area.

McCulloch is survived by daughters Michaele Lee (Dee Dee) Parman and Candace Sue (Candy) Akers of Santa Rosa, CA. He was preceded in death by wife Jakie Caldwell McCulloch, son David Caldwell McCulloch and sons in law Mike Parman and Ron Akers. He is also survived by grandchildren Christopher T. Parman and Leah M. Parman, step grandchildren Elizabeth A. Akers and Erica L. Akers, great grandchildren Sienna P. Clark, Alden L. Clark, Cole A. Parman, Jake R. Parman and Zachariah L. Akers.

A memorial service was to be planned. In lieu of flowers, donations may be sent to the Frank McCulloch Courage in Journalism Award Program at the Reynolds School of Journalism, University of Nevada, Reno Nevada, UNR Foundation, MS0162, Reno, NV. 89557.