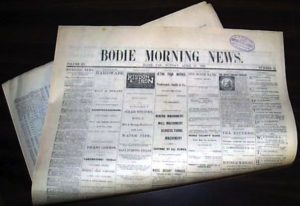

The Bodie Morning News

The streets of this once-thriving town are deserted, populated by a smattering of buildings and other signs of the past. But in its heyday, as many as 10 newspapers chronicled the life and times of Bodie. Then, like dust in the wind, the miners, merchants and townspeople were gone.

Story & Photos by Jim Toland

When newspapers fail, it’s usually because they can’t survive an evolving community business change, advertising model or news standard. It’s rare that papers fail because an entire town they serve goes under. But that’s what happened when one large Northern California gold mining community went bust in the early 1880s.

Today, Bodie’s 75 abandoned buildings face lonely dirt streets. Some structures are just piles of broken wood topped with the remains of a peaked roof. Others have endured, their rooms visible through partially missing walls.

Peeling wallpaper, much of it just shreds of ancient newspaper used to seal cracked wooden walls, hangs limply. Broken antique furniture, cracked iron stoves and rusted remnants of printing equipment have been dumped outside under wild clumps of yellowed brush. Sporadic desert breezes lift and whirl bits of debris about dusty streets.

Peeling wallpaper, much of it just shreds of ancient newspaper used to seal cracked wooden walls, hangs limply. Broken antique furniture, cracked iron stoves and rusted remnants of printing equipment have been dumped outside under wild clumps of yellowed brush. Sporadic desert breezes lift and whirl bits of debris about dusty streets.

Over the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada, the rising sun glints off mining equipment and ancient automobile parts. It is dawn in Bodie, Mono County, the largest unrestored ghost town in the West and one-time home to a solid handful of daily newspapers. Now the ruins mostly attract historians, writers and photographers seeking unique subject matter devoid of human interference.

THE FIRST NUGGETS

When James W. Marshall reached into the tailrace of Sutter’s Sawmill in the Sierra Nevada foothills — January 1848 — to probe for a few flecks of yellow metal beneath the water, he sparked the largest mass migration in American history.

Within the next seven years fortune hunters and prospective miners flocked to Northern California from every corner of the globe. They were called 49ers, named after the first big year of the gold rush. With them, came every kind of 19th Century merchant and service vendor imaginable along with the presses to advertise products, bars and brothels — and report the news of the day.

Newspapers ran the shootings under a standing headline: Last Night’s Killings.

Bodie came late to the gold rush. The town was named for Waterman S. Body (spelling later changed by a cleric to preserve “decency”) who, in 1859, according to legend, was riding through the area, shot a rabbit, started to dig it out of its hole and in the process discovered gold. News of the discovery traveled fast and soon miners who had failed to strike gold or silver earlier on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada were heading toward the high desert country and Bodie. In 1876, strikes in two mines made Bodie a prominent mining center.

By 1880, Bodie was one of the wildest towns in the West and boasted a population of 10,000. Miners, gamblers, prostitutes, shopkeepers and thieves packed the streets of the booming town. In its prime, there was in average of six killings a week.

The town’s two largest daily newspapers — The Morning News and The Evening Standard — ran the shootings under a standing headline: Last Night’s Killings. Great fodder for newspaper reporters scraping out an existence in a lawless community.

They also published extensive reports about mining, finance, newly opened businesses and entertainment.

Other Bodie newspapers published from 1878-82, and available today for review at The Library of Congress, include:

- The Chronicle

- The Daily News

- The Evening Miner

- The Mining Index

- The Evening Union

- The Free Press

- The Standard-Union

- The Weekly News

A Methodist minister described Bodie in 1881 as “a sea of sin, lashed by the tempests of lust and passion.” It was the minister who insisted the name of the town be changed to Bodie from Body, which apparently seemed suggestive at the time.

Bodie, with a main street more than a mile long in 1879 and with the West’s largest Chinatown outside of San Francisco, was a 24-hour operation. Nothing from the mines to the saloons ever closed.

Pack trains and stagecoaches arrived daily with passengers intent on grabbing what wealth they could from the mines or the miners.

Rugged, violent, excessive town that it was, Bodie was a heavy gold producer. Between 1878 and 1881 nearly $30 million in gold and silver was taken from the 30 mines drilled in the side of Bodie Bluff. More than $95 million (1880 value) was taken out of the hill during the town’s mining history.

BEGINNING OF THE END

The demise of the heyday began in 1882 then there was a stock failure and two of the larger mines fizzled. Soon afterward, the smaller diggings began to die. By 1888 there were only three working mines left out of 10 times that number a few years before. On July 25, 1892, a fire destroyed all but a few buildings in Bodie’s business district. On June 23, 1932, a boy playing with matches started a blaze that gutted all the buildings left in the town—save the 75 now to be seen. Also surviving is the cemetery, which lies a few hundred yards west of town.

“Fine progress” on a mine.

The infamous “Badman from Bodie,” a character dramatized by Mark Twain, who was then working as a newspaper reporter on the Virginia City Enterprise, is a familiar name to western enthusiasts. Several historians say he was a real person, Tom Adams. Others say that there have been so many bad men and women in Bodie that it could have been anyone or a composite of several evil characters, including Washoe Pete, James De Roche, Shotgun Heilshorn, Two-gun Al, Madame Mustache, or Emma Goldsmith.

None of the buildings in Bodie — about 260 miles east of San Francisco and seven miles from the Nevada line — has been reconstructed, none of the paint has been touched up. The garbage hasn’t been picked up in more than 80 years. The town, designated a state park in 1962, remains, except for decay, the way it was after the last of its citizens left after a final fire in 1932.

There are other so-called ghost towns in California: Most are in gold rush country between San Francisco and the Sierra. A few still stand east of the Sierra, south to the Mojave Desert and in the far northern areas of California. Some of these “ghost towns” are actually populated communities. Others, while deserted, consist of no more than three or four buildings.

Bodie, however, is a sizable deserted community, for while much of the original town has been destroyed, the 75 buildings remain. Some of them: the Methodist Church, the firehouse, the school, the blacksmith shop, a saloon, Bodie Jail, a general store, the Standard Mine, the Oddfellows’ (IOOF) Lodge. The Miners’ Union Hall now houses a small museum (open only in August) which contains original town relics, including guns, clothing, school books, mining equipment and artifacts from some of the saloons.

Bodie becomes visible after a 13-mile drive over a narrow, bumpy, twisting road off U.S. 395 — open only from late spring until the snow falls in November. At the top of a hill, overlooking the town, which is at more than 8,000 feet, it is difficult to imagine that it was once a gold mining settlement with a population of more than 10,000 and a collection of 65 saloons.

The 1880 U.S. Census put the official population at 2,712 — but most residents at the time weren’t the kind of upright citizens who might participate in a process revealing their private info. Either way — 10,000-plus or 2,700-plus — the Census numbers compare to a Los Angeles 1880 figure of 11,183.

THE DECAY TODAY

Since becoming a State Historic Park, Bodie is kept in a condition of arrested decay. It is not being restored, but it will not be allowed to deteriorate as rapidly as it did before the state took it over. As for changes, the state is touchy about them: If a window is replaced, for example, it must be done with vintage glass.

Bodie’s only inhabitants are two state park rangers who reside the year round in a couple of the town’s better-equipped shacks. The rangers keep quietly out of the way, and during the summer months they are usually under buildings shoring up floors or strengthening foundations.

Before the rangers arrived in 1962, visitors carried off the town’s remaining artifacts and antique furniture. They vandalized the buildings and smashed windows. But for the rangers, there wouldn’t be much left to see in Bodie. Now there will be a standing monument to the Old West for future generations to visit — so long as they can make the slow, careful trip over the 13 miles of bumpy Bodie Road.

SHOOTING UP BODIE

Enjoy a people-free photo shoot? Go to Bodie.

From San Francisco: Take Interstate 580 to Manteca, then State Route 120 through Yosemite National Park to U.S. 395 at Lee Vining, turning north to Bodie Road.

From Los Angeles: Follow I-10 toward Riverside, pick up I-15 north and then drive northward on U.S. 395 to Lee Vining.

There are no public phones, no restaurants, no motels, no gas stations and no souvenir shops in Bodie. There are, however, motels and restaurants in both Bridgeport (20 miles away) and Lee Vining (31 miles away).

Many of Bodie’s pioneers were transplants from Columbia, the largest town in the Southern Mines during the 1850s. The population reached more than 15,000 and the town bustled with the activities of merchants, gamblers, and prostitutes ready to do business with the miners. The town contained 40 saloons, 143 faro games, and an arena for bear fights.

Columbia burned down several times, the worst fire razing the town in 1854. It was finally rebuilt as a shadow of itself in brick with iron shutters and fireproof doors.

Among the more interesting traditionally restored sites in Columbia are: Wells-Fargo Building, IOOF Hall, Fallon Theater, town jail, City Hotel, a Mexican fandango ball circa 1850, a Chinese store, the park museum, and several miners’ cabins and a boarding house. An operating quartz mine near the park is open for tours.

Columbia is easily accessible off California Highway 49 and popular with tourists. But, in contrast to Bodie, there are many more people than ghosts.

Jim Toland is a retired San Francisco Chronicle editor and retired San Francisco State University journalism instructor who has written several novels including the recent Fire And Fog and Once Were Wolves.