For photojournalist Randy Davis, four decades at KGO-TV began with voice-overs and weather photos and led to some of the biggest news events in the country. One of the highlights was working with his father, the acclaimed reporter and anchor Steve Davis.

By Kevin Wing

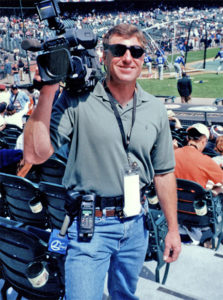

It seems impossible to think that the keen photographic eye of Emmy Award-winning

photojournalist Randy Davis would not have graced Bay Area television screens these last 40

years had it not been for the fact that business school just wasn’t working out for this

son of a veteran San Francisco television news reporter and anchor.

Randy Davis

But what came to be is a television career that has now spanned four decades. And at the same San Francisco TV station. Who achieves that? Not many. The Bay Area television market is not only one of the most sought-after in the United States, making it one of the most competitive in the business.

But Davis — who was inducted into the Silver Circle of the San Francisco/Northern California Chapter of the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences in 2016 for his more than 25 years of contributions to the industry — has, without doubt, succeeded.

In 2019, he is celebrating his 40th year at KGO-TV ABC7 in San Francisco. While most aspiring photographers, reporters and producers need to toil away in the small TV markets after college, Davis started his career at KGO.

In the interest of full disclosure, Randy’s father, the legendary Steve Davis, was one of the

station’s most prominent anchors and reporters at KGO-TV in 1979, the year Randy started at

the station as a stringer, or freelance photographer. And while some at the time might have

cried nepotism, suffice it to say that while his father did work at the station — from the early

1970s to the early 1990s — Randy never wanted to follow in his Dad’s footsteps.

“I was in business school, and I decided I didn’t like business school,” Randy Davis said. “But I

was foundering. And I was wondering what I was going to do. And so I thought I’d give TV

news a shot. My Dad tried to discourage it. He thought, ‘Well, you know it’s a good industry, but

I’d rather see you do something else.’ ”

Randy said “that’s the truth of it. I never had any intention of being in this business.”

Nevertheless, it was Davis’ destiny. In fact, he still remembers his first day at KGO-TV.

“I was a stringer,” he said. “Of course, we all start out that way, stringing, and stringing with

other freelancers, competing for opportunities to work. And so, the first day, it was like ‘Who

wants to work with the new kid?’ But it was different, because through my Dad working at the

station, I knew all of the reporters. And they knew me.”

At first, Davis said, he did voice-overs and read live scripts leading to video/audio sound bites, and usually was the one to shoot a pretty weather shot.

He also remembers reporter and anchor Suzanne Saunders (Shaw) as the first reporter he

worked with.

Davis remembers being “overwhelmed, and trying too hard.” He said he ended up being “very

klutzy”.

Saunders told him he was doing a good job, but that he spent too much time setting up lights

and trying to get the right camera angles.

“This is the business of getting things done,” Davis said. “I learned that right away from

Suzanne. Most of the time, we don’t have the luxury of spending a lot of time on each shot. We

almost intuitively know what we need to do, and we get it done.”

In those days, Davis worked with many reporters, including Ed Leslie, Carol Ivy, Lee

McEachern, Peter Cleaveland and Don Sanchez, who ended up remaining with

the station for four decades.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, TV was still young, Davis said. A lot of people who worked in

newspapers and magazines were coming over to work in TV news. The industry, he said, was

still going through a growth period.

Before KGO-TV moved into its current ABC Broadcast Center location on Front Street in San

Francisco in 1985, it was housed in cramped quarters on Golden Gate Avenue in the city’s

seedy Tenderloin neighborhood.

“That newsroom was cramped and tiny and it was wonderful,” Davis said. “What could be

better? It had what we don’t get enough of now. It had personality. TV news was meant to have

emotion. It needs that and it flourishes in that. We had that back then. People used to shout at

each other over the typewriters back then. Everyone got it. It wasn’t being vicious. It was what

we did. They were excited about what they were doing and they liked it.”

After three years of freelancing at KGO-TV and at KTVU in Oakland and KICU in San Jose, the

station finally hired Davis full time. Since then, he has nearly done it all.

Davis covered the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989, the Oakland Hills firestorm in 1991, the

Oklahoma City bombing in 1995, all national political conventions, Super Bowls and

more. He was sent to New York City after the Sept. 11 terror attacks in 2001.

“We couldn’t get a flight out of the Bay Area for New York, so we ended up driving there,” Davis

said of his work with then-KGO-TV reporter Jim Wieder. A few days later, they arrived.

“New York is a busy, noisy place,” Davis said. “When we got there, it was absolutely silent. I

don’t know what I was expecting. Everyone was starting over again. People really didn’t know

what to do with themselves.”

The story that Davis said has affected him the most was the 1999 massacre at Columbine High

School in Colorado, where 12 students and a teacher died in a mass shooting at the hands of

two senior students.

“It was bad,” he said.

The mass shooting in 2012 that killed 26 children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary

School in Newtown, Connecticut, was “emotionally devastating”.

“We got on a plane as soon as we found out, (reporter) Laura Anthony and me,” Davis said.

“We went straight to the school. When we got there, we saw people from everywhere

assembling. They needed to share the loss of what everyone was experiencing. Some 2,000

people stood around the school not because they wanted to see what had happened, but to

share the loss of what everyone experienced. Usually, when you have 2,000 people together in

one area, you have noise. All we heard was the shuffling of feet and people crying and

sobbing.”

Davis said “there is a payoff for all of this bad.”

“We’ve all done a lot of stories that have taken us everywhere,” he explained. “We’ve seen

many Super Bowls, basketball championships, World Series. We’ve seen a lot of fun things.

We’ve experienced a lot.”

But for every story Davis has covered that involved tragedy and loss, there is this takeaway:

“We all care about people,” he said. “We are human, and when people are hurting and suffering,

we acknowledge it.”

Davis’ experience as a photographer during his earliest years at KGO-TV was enhanced by the fact that he got the occasional opportunity to work with his father, Steve, who

passed away in 2005.

“We always enjoyed each other when we worked together, my Dad and me,” Randy Davis said.

Steve Davis was an award-winning reporter and anchor at KGO-TV from 1971 to 1991. He

covered most of the major stories of that era, from investigating the Rev. Jim Jones and his

People’s Temple group in San Francisco before more than 900 of Jones’ followers died in a

mass suicide in Guyana, to extensive reporting on the Symbionese Liberation Army, the group

that kidnapped newspaper heiress Patricia Hearst. In later years, Steve covered the

devastating Oakland Hills firestorm.

One story the Davises worked on together was revisiting Washington State’s Mount St. Helens

volcano, 10 years after it erupted in 1980. That year, Steve covered the eruption with

photographers Clyde Powell and Guy Hall. In 1990, he and Randy went there to explore the

volcano’s crater first hand.

“We flew to the top of Mount St. Helens,” Randy said. “It was a beautiful day, a gorgeous day.

We looked down at this smoldering cauldron. It was so cool, so neat. We were up there for a

number of hours getting shots and doing interviews. Then, as will happen in the mountains, the

weather changed swiftly and a storm rushed in. We were just finishing up my Dad’s stand-up

when the pilot shouted at us to get back in the helicopter right away.”

The pilot said later that had they not taken off immediately, the three would’ve been stuck on the

mountain for days.

“So we strapped up,” Randy said. “The chopper takes off as fast as the pilot could fly it out of

there. He scared the shit out of us, actually. The pilot flew the chopper down the side of the

mountain, then dropped it straight down to get out of the clouds, almost vertically, and all the

while, we couldn’t see very well.”

On the way through the storm clouds, they narrowly missed hitting high-voltage power lines.

“We missed it,” Randy explained. “And in the end, we got the tape back (to the station). That’s

what was important.”

Randy said his father loved horses, so when the opportunity for the two of them arose to do a

story about wild horses in Nevada, they jumped at the chance.

“I got to do those really fun things with my Dad,” he said.

The two ended up having the chance to work with each other for nearly two decades.

Davis cherishes the visual memory he has of his father at work. It dates back to when the

station was located in the Tenderloin.

“I’d go visit him at his office at the old station,” Davis said. “He’d be sitting there in his tiny little

office. He would be typing out a story on the typewriter. He couldn’t type, so he used his two

index fingers. His feet were always tapping on the floor while he typed. A cigarette hanging from

his mouth, a cup of coffee nearby. I’ll never forget my Dad.”

Kevin Wing is senior correspondent for “Off Camera,” a monthly publication of the San Francisco/Northern California chapter of the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. He is also a chapter governor.