“Nice guy. Good photographer,” the young editor said after poring over pictures from Joe Rosenthal. Then came the realization: This wasn’t any old Joe. This was the photographer who riveted the world’s attention with one of the most famous photos from World War II.

By Jim Toland

One of the great things about working in the news media is meeting remarkable people. Even better, working closely with them.

My first few weeks at The San Francisco Chronicle – just out of San Francisco State – were a madhouse. The newsroom buzzed erratic and ecstatic in the turmoil of Richard Nixon’s resignation and its immediate aftermath.

While the staff was absorbed in world-changing history, my time, contrarily, was spent in the rear of the newsroom, temporarily taking over as Business World section editor where I’d select daily wire and local stories and photos, edit and crop, write headlines and captions, design pages, format stock market tables, then move to the composing room to work with typographers to make it all fit and get the pages to the engraver and on the press.

Never panicked, but constantly stressed, I spent my early newspapering days in 1974 in a blur of note-taking, questions and fly-by introductions – a one-man band in the fading pre-computer, manual typewriter, linotype era of big-city newspaper production.

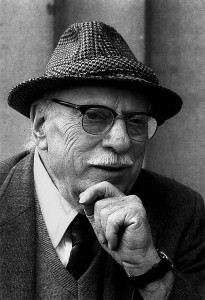

One day I awaited contact sheets from a staff photographer who had covered a local event. From behind a cubicle wall separating Business World from the City Room and the Library emerged what I then thought of as “an old guy” (he was younger then than I am now). He wore a black beret over frosty hair and the thickest glasses above a bushy white mustache. He wasn’t tall and, standing, could face me straight on as I sat drowning in piles of marked-up copy paper.

“Hi, I’m Joe,” he said, calmly extending his free hand. “Brought your contact sheets.”

“Great,” I snapped, sharing my name and quickly gripping and releasing his hand. “Just put them in the basket and I’ll call you when I pick a shot.”

Joe seemed disappointed. “Maybe we can look them over and discuss them.”

Though every second counted in this tumultuous editing routine, and I wanted to scream, “I’m on deadline – get out,” the part of me that I like best, said, “Sure, sit down.”

Joe reviewed my draft page layout, then counseled me to adjust the photo placement from horizontal to vertical for more impact. He offered some notes he’d taken on site, which improved our reporter’s story. When he rose to go, I thanked him and immediately regretted saying: “Stop by any time” – fearing he might again disrupt my wound-too-tight editing flow.

“Maybe, if you’re not too busy,” he replied, obviously sensing my newsroom angst.

♦

When the issue went to press, I brought a page proof to the news desk for critique.

“Not bad, for your first weeks alone on the job,” said Ken Wilson, news editor. Staring at the photo, he asked. “How’d you like working with Joe?”

“Fine. Nice guy,” I said, neutrally. “Good photographer.”

Wilson laughed. “You don’t know who he is, do you?” Without waiting for any reaction: “That’s Joe Rosenthal, the most famous photographer in America. He won the Pulitzer Prize for his shot of the flag-raising on Iwo Jima. You’ve seen that photo?”

Of course. Everybody had. I couldn’t remember feeling stupider as my mind raced back to my encounter with Joe and every word we had exchanged. I hoped he hadn’t felt insulted, too brushed off. My stomach churned.

♦

That night, after the final edition was running on the presses, I sat at my desk and reviewed Chronicle Library clippings about Joe Rosenthal and Iwo Jima. (And, while I violate newswriting rules, he is best known as “Joe” in stories, not “Rosenthal.”)

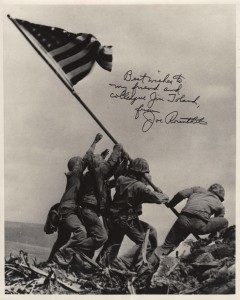

Joe’s black-and-white photo of five weary Marines and a Navy corpsman struggling to raise an American flag on Feb. 23, 1945, was taken while on assignment with the Associated Press (AP). It was the most widely reproduced image in U.S. history – immediately featured on magazine covers and in hundreds of newspapers. The Treasury Department

printed it in 1945 on 3.5 million posters promoting a war-bond campaign that raised $26.3 billion (yes, billion).

Soon after, the U.S. Post Office, honoring the Marine Corps, engraved the image on three-cent stamps that broke records for first-day cancellations. The photo later

became a three-dimensional, 110-foot-high, 100-ton bronze Marine Corps War Memorial sculpture near Arlington National Cemetery.

The Pulitzer Committee in 1945 described the Joe Rosenthal photo as “depicting one of the war’s great moments,” a “frozen flash of history.”

Joe was born to immigrant Russian parents in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 9, 1911. He reportedly selected his first camera at age 12 from a catalogue in exchange for cigar-store coupons. A year after finishing high school, the Newspaper Enterprise Association hired him in 1930 as an office boy. The San Francisco News, two years later, brought him aboard as a reporter-photographer. When the first planes bombed Pearl Harbor, Joe was already an AP photographer in the San Francisco bureau.

He was eager to serve his country and tried to enlist in the military at the beginning of U.S. involvement in World War II. He was declared unfit for duty because of extremely poor eyesight. Joe, however, was able to join the U.S. Maritime Service and served a year as a warrant officer, documenting life aboard ship in Europe and Africa. Few military veterans of the war would see as much action, close-up, as Joe eventually did. At the beginning, he crossed the North Atlantic in a Liberty ship convoy attacked by German U-boats and covered the Blitz in London.

Then, he obtained official war photographer credentials in 1944 and shipped out to the Pacific, again working for AP. He photographed Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s Army fighting in the New Guinea jungles. He experienced war at sea in the South Pacific aboard an aircraft carrier, a battleship and a cruiser. He flew with Navy dive-bombers destroying enemy targets in the occupied Philippines.

At 33, Joe accompanied early waves of a 70,000-man Marine force on Feb. 19, 1945 that was ordered to seize Iwo Jima – 7.5 square miles of black volcanic sand about 660 miles south of Tokyo. The island, defended by 21,000 Japanese soldiers, held airstrips needed as bases for American planes.

By the fifth day the Marines had quelled Japanese opposition and those remaining soldiers dug into caves on Mount Suribachi – a 546-foot-high, extinct volcano on Iwo Jima’s southern tip.

♦

The next day after my initial Chronicle intro to Joe, he appeared at my desk.

“Turned out pretty good,” he said, holding the morning newspaper, open to the then-green-colored Business World section.

“Hope I didn’t rush you yesterday,” I said, feeling inside like Jackie Gleason appeared on TV when a Ralph Kramden scheme went south. “Tight deadlines.”

“No. You looked swamped and sometimes I can go on awhile. I enjoy meeting people.” Then, from nowhere, he asked, “Are you a veteran?”

The Vietnam War was still burning up Southeast Asia at the time – though U.S. forces had withdrawn just the year before – and most of the men and women who served during the unpopular conflict didn’t speak much of it in the 1970s, at least not in San Francisco.

“I served as a low-ranking orderly in an Army rehab hospital,” I said. “No combat. Just helping wounded soldiers to get moving and get on with their lives. Don’t talk much about it. Pretty awful all the way around.”

Joe nodded. “Always is.”

A few nights later he popped by and we chatted about North Beach and Telegraph Hill where he lived and from where my family hailed.

Then I cleared my throat and asked about the flag-raising.

♦

“By mid-morning, on that fifth day of attack, a group of Marines raised a small American flag at the summit. Marine Sgt. Louis Lowery photographed the event,” said Joe, shifting almost into automatic pilot as one might who has told a story far too many times.

“A few of us [combat photographers] were told about the first flag-raising and we went to the summit, where we spotted men from the 28th Regiment, Fifth Division, preparing to raise a second, larger flag – one that could be seen easily by Marines all over Iwo Jima and by sailors on the ships offshore,” Joe explained.

“I climbed down just inside the [volcano] crater lip to set up sharper focusing distance, then propped myself on rocks and an abandoned Japanese sandbag so I could see over some brambles [he was 5 feet 5 inches tall].”

Joe saw Marines securing a larger flag to a pipe. Other Marines stood ready to simultaneously lower the smaller flag as the bigger one rose. He focused on the larger flag (8 feet by 4 feet, 8 inches) and, as it began to ascend, he quickly turned to the action and snapped the shutter.

“I took the picture; the Marines took Iwo Jima.”

He later told a camera magazine that he set his Speed Graphic camera lens between f/8 and f/11 and speed at 1/400th second. Speed Graphic was then the standard for press photographers.

♦

The photo immediately resonated with Americans at home especially because it honored the first seizure by U.S. troops of land designated part of the Japanese homeland. The image is still regarded as a symbol of Marine Corps fighting spirit.

The flag-raising was just the beginning of the ferocious fight for Iwo Jima. Joe took the photo on the fifth day of the raging 36-day battle that killed 6,621 Americans and wounded 19,217. Nearly 22,000 Japanese defenders were slain leaving only 1,083 survivors before the island was captured.

Wartime Navy Secretary James Forrestal said of Joe Rosenthal at the time: “He was as gallant as the men going up that hill.”

Joe had already hit the beaches with the first Marine waves landing under fire on Guam, Peleliu and Angaur. He was among the first ashore on Iwo Jima.

“The situation was impossible. No man who survived the beach can tell you how he did it. It was like walking through rain and not getting wet,” Joe often said.

♦

After World War II, Joe Rosenthal briefly returned to the AP in San Francisco. He joined The Chronicle in January 1946 and stayed for 35 years until his 1981 retirement.

One Monday evening, about seven months after we first met, Joe plopped himself down next to me on the news copy desk, where I was then assigned, and unloaded a Sunday (March 3, 1975) New York Times from the day before. It landed with a thud. He flipped through the pages and came upon a feature and two photos I had sold to the “newspaper of record” – with byline and photo credits.

“Good work,” he said. “Nice layout above the fold. Didn’t know you could handle a camera.”

“Me telling you I can handle a camera would be like me bragging to Muhammad Ali that I pack a solid punch. Not going to happen.”

As we caught up a little, I could tell Joe was distracted. Finally, he said, “It’s frustrating. Someone here made a snide remark that my Mount Suribachi photo was staged. It wasn’t, you know. I just got an incredible break.”

Intuitively, I believed Joe. As a journalist, I spent time searching the facts—then and later.

♦

From the first day that the photo hit newsstands, suspicions arose that Joe staged the image, posing the Marines. He always insisted he shot an honest event, and others present that day have corroborated his story.

“The picture was not posed,” said Louis Burmeister – a former Marine combat photographer among the four military photographers alongside Joe as the flag rose – in a 1993 interview for “Shadow of Suribachi,” a book by Parker Bishop Albee Jr. and Keller Cushing Freeman.

“If it was posed, we would have probably had their faces toward us,” Burmeister said. “You notice, in the picture, nobody’s facing us.”

That corroboration, reported The New York Times, was supported by a color film of the flag-raising, photographed by Marine Sgt. William Genaust, a combat cameraman, at the same time from nearly the same vantage point. It shows the flag, affixed to a pipe, going up in an unbroken sequence.

Joe said he was lucky to catch the flag-raising at its “most dramatic instant.”

“The sky was overcast, but just enough sunlight fell from almost directly overhead, because it happened to be about noon, to give the figures a sculptural depth,” he wrote in Collier’s magazine on the 10th anniversary of the flag-raising.

“The 20-foot pipe was heavy, which meant the men had to strain to get it up, imparting that feeling of action,” he wrote. “The wind just whipped the flag out over the heads of the group, and at their feet the disrupted terrain and the broken stalks of the shrubbery exemplified the turbulence of war.”

“To get that flag up there, America’s fighting men had to die on that island and on other islands and off the shores and in the air,” Joe wrote. “What difference does it make who took the picture? I took it, but the Marines took Iwo Jima.”

“The characters create an ascending motion, but they’re frozen in time in a brilliantly precise way,” Alan Trachtenberg, author of “Reading American Photographs: Images as History, Mathew Brady to Walker Evans,” said in a 1997 interview with The New York Times. “And it’s more than just raising a flag. It’s a sense of culmination, of triumph, not just over an enemy but over the challenge of war itself. It’s become an iconic image, like Uncle Sam.”

The erroneous, unfair photo-staging accusation would haunt Joe throughout his career — despite solid evidence proving otherwise.

♦

When he retired from The Chronicle in 1981, Joe, always humble, described himself as “just a newsman with a camera.” According a Chronicle story, he made little money from the Iwo Jima photo. He believed it was less than $10,000 altogether.

“And I was gratified to get that,” he said in a 1995 Chronicle interview. “Every once in a while someone teases me that I could have been rich. But I’m alive. A lot of the men who were there are not. And a lot of them were badly wounded. I was not. And so I don’t have the feeling someone owes me for this.”

Joe Rosenthal was elected president of the San Francisco-Oakland Newspaper Guild in 1951, twice president of the San Francisco Press Club, and three times president of the Bay Area Press Photographers Association.

He held numerous honors, and a degree from the University of San Francisco, but was proudest of his framed certificate declaring him an “Honorary Marine.”

I left The Chronicle in 1987 after working news, features and business assignments for 13 years and had lost touch with Joe until he popped up at my aunt’s funeral in 1990. Unknown to me, she was a longtime friend and neighbor of Joe’s on Telegraph Hill.

“Small world, many connections,” said Joe as we parted. He died peacefully in his sleep Aug. 20, 2006 at age 94.

My office walls display articles, awards and other mementos of my career as a journalist, but I am proudest of a framed flag-raising photo hanging over my desk declaring: “Best wishes to my friend and colleague Jim Toland from Joe Rosenthal.”

♦

Jim Toland, author of several novels, teaches journalism at San Francisco State. A former San Francisco Chronicle editor, he’s a media communications consultant who has worked for the Clinton White House and The New York Times among other organizations. He is an editorial advisor for the Northern California Media Museum. He’s also Adjutant Officer for American Legion Post 599 in San Francisco’s North Beach.